Does Your Moral Character Commune Understanding and Respect for Human Dignity?

Part III: Where you stand requires understanding the moral myths that organize society.

In part I and part II of this series I discussed the qualities that define our humanity and support one’s integrity. These qualities include your natural and desired character traits, your core values, and the beliefs that orient you within society. Knowing these qualities will support where you stand in life, but without a meaningful and actionable purpose, you won’t have clarity or direction about where you’re going in life and why.

In this article, I will dive into the much bigger picture: Where do you as an individual ground yourself in the larger, moral landscape to commune with the rest of humanity in a balanced way?

What Is Your Moral Character?

Remember the metaphor of the house from, “Is What You Stand For In Life Making a Meaningful Difference in the World?”

“Think of a stately mansion that has been around for hundreds of years, beautifully maintained, and made of large blocks of stone. It’s a solidly built structure that looks impervious to severe weather and the wear and tear of time. What you don’t see are the foundations deep below that support the integrity of the structure.”

Your moral character is like the property or the ground on which your house stands. We all commune on a moral landscape, putting our stake in the ground regarding what we believe, what we stand for, and establishing the communities to which we belong.

How would you describe your moral character if someone asked you to tell them in one to two sentences?

There’s an important reason behind why I am using the word, commune:

As a verb, commune means, “to converse or talk together, usually with profound intensity, intimacy, etc.; interchange thoughts or feelings; to be in intimate communication or rapport: to commune with nature.” (Source)

When we commune with others, we are going beyond the simplistic aspects of simple communication, of imparting bits of information. Communing with someone is making a deeper connection, seeking oneness with them which is a form of understanding and respect for their dignity as a human being.

In this age of internet doxing, bullying, and cancel culture, we need to be reminded of the need for connection and belonging. The more we push away or condemn others and declare ourselves on the “right side of the argument” the more likely we are to dehumanize those we disagree with and create further division and polarization.

Society defines and supports various moral landscapes in the form of organizational myths.

We witness these moral landscapes in the form of religions, each one ascribing a set of group beliefs and values that are usually attributed to a higher power and outside individual interpretation. The exception to the rule is the religious ‘leader’ who manipulate the narrative to ‘his’ advantage. I specifically use the gendered ‘his’ because most dogmatic and fundamentalist religions are led by men, which depends upon followers blindly believing in the associated myths of gender and patriarchy — both used as forms of social organization and control. Not all religions are like this, but the problem is endemic.

We also live with the organizational myth of politics, be that liberalism, socialism, populism, oligarchic governments, dictatorships, and capitalism. You might suggest that capitalism shouldn’t be labelled under politics. Capitalism, however, has been the single largest unifying organizational myth of all time. Yuval Noah Harari makes a powerful case for this argument in his book, “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.”

Capitalism has allowed people and countries to work together using a system of exchange and evaluation across borders, language, and customs that everyone understands. Good or bad, everyone knows what money is, which in and of itself is another myth. Currency, like time, is an intellectual construct. If you don’t agree that capitalism isn’t political, consider why governments are involved in taxation, tax breaks for corporations, and in some cases, ownership of so-called Crown corporations.

The variety and difference of myths organizing society lead to contentious questions of morality and justice.

For an endless supply of examples, review a reliable, factual, and trustworthy source of news media. Here is a broad cross-section of current moral issues:

- An Oligarch’s attempt to limit a powerful voice standing in opposition to his life-long power and control over a country (by resorting to a failed poisoning attempt and a bogus court case which did nothing to quell dissenting citizens): “Russia is progressively disconnecting itself from Europe and looking at democratic values as an existential threat.” (Source)

- Conflicts across the globe based on religious myths: “The practice of burial, and the associated religious rituals and practices, are central tenets of the Islamic faith, a faith which is practised by a persecuted minority in Sri Lanka.” (Source)

- Secret myths that control the myth of democracy but only subvert it to the betterment of those in power: “The anti-democratic potential of the [Queen’s] consent process is obvious: it gives the Queen a possible veto, to be exercised in secret, over proposed laws. But there has been no way to know whether it was realising that potential or not, and so no way to know how damaging the process might be, because its workings have previously remained hidden from public view.” (Source)

- A populist government creating “LGBT-free zones”: “A Dutch town has severed its longstanding ties with its twin in Poland after the Polish municipality established itself as an official “gay-free zone”.” (Source)

- A political party in disarray because more than half of its members are megalomaniacs, believe in conspiracy theories, and find truth and facts to be inconvenient: “[Marjorie Taylor Greene] has blamed California’s wildfires on a Jewish laser beam from space, claimed 9/11 was an inside job, and suggested that school shootings were staged. In 2018 and 2019 she endorsed social media comments that appeared to support the assassination or execution of Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi… 95% of the chamber’s Republicans refused to strip the freshman member Marjorie Taylor Greene […] of her committee assignments.” (Source)

- Aboriginal cultural dress versus a dress code based in colonialism: “The Māori party co-leader Rawiri Waititi has defied the order to wear a tie in the New Zealand parliament’s debating chamber — and was promptly ejected by the Speaker.” (Source)

Why can’t we all just get along?

In a world of close to 8 Billion people, the solution to that rhetorical question seems as complicated as solving the origin of the Big Bang and discovering what, if anything, came before it.

At the moment, we are a species connected by our shared humanity but ever-more separate thanks to the liberalism myth of individuality. We are living in a paradoxical duality: our humanity connects us, but it doesn’t necessarily protect us. This is especially true for LGBTQ peoples in places like Poland or Chechnya. The dominant religious myth and political parties have deemed our lives a threat to societal mores and values — or that we are non-existent entities, i.e., we simply do not exist in their country. (Feel free to replace LGBTQ with any other marginalized identity or group of people.)

The cult of identity, at its worst, sees humanism as a lack of personal liberty. In other words, there is a lack of communing with the other.

Let’s come back to the organizational myths that manage and control societies. While some myths connect us (like capitalism), others, like dogmatic religions and oppressive political regimes, dehumanize and thus disconnect us. There is nothing more powerful than fear and disgust to motivate groups of people (including an entire country) to agree to restrictive laws and harsh criminal sentences in exchange for the prediction and response of what you are told to believe (a form of indoctrination) that will keep you safe (as promised by a patriarchal state).

A Universal Moral Code: Possible Utopia or Pipe Dream?

There is a larger debate about whether human values can and should be considered facts, in particular, if those values are shown to contribute to the overall well-being of humanity.

For example, could compassion, when regularly practiced, be observed and measured as having a demonstrable improvement over individual and group well-being, both by the giver and the recipient? It’s an important and vital question in the discussion about a universal moral code, one which Sam Harris discusses in his book, “The Moral Landscape.”

Without going down the rabbit hole of whether moral values can be factual, I hope you would agree that we are missing a universal moral code. This includes those who want a moral code based on religious imperatives, however, this is precisely where we get to deal with the issue of dehumanization head-on.

Without a shared understanding — a way to commune on an even landscape — we risk ever more contention and division. We need to know what we stand for individually and collectively.

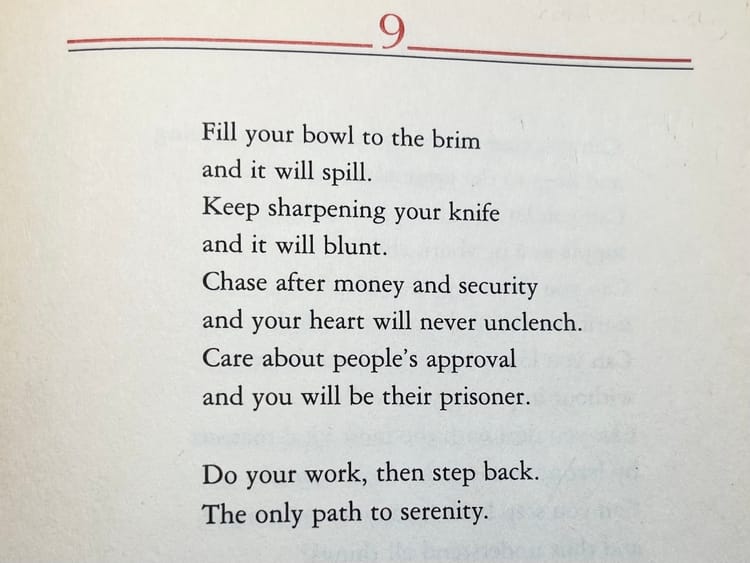

In the next instalment of this series, I will share a set of transcendent values based on the wisdom and interpretation of the Tao Te Ching. I believe these “principles” are values that everyone would agree surpass and exceed other individual values in the service of cultivating a better society and humanity.

Member discussion