An Intergenerational Conversation With Gay Activist Ken Popert

Think Queerly Podcast Leadership Interview with Co-Host, Jeff Iovannone — TQ216

Today’s episode is the result of an intergenerational intersection. As Jeff Iovannone (joining me as co-host) says in the introduction, the work that Ken Popert did while he was a graduate student at Cornell University in 1968 has impacted what students are doing 50+ years later.

Ken’s name kept showing up in the historical research Jeff has been doing at the Human Sexuality Archive at Cornell, and for one of his courses, “Making Public Queer History.” Jeff recognized Ken’s name because I used to work at Pink Triangle Press (PTP) in Toronto, Canada where Ken was my direct report. I also talked about PTP, and its founding publication, The Body Politic, in an interview (with Jeff as co-host) with the authors of “Out North: An Archive of Queer Activism and Kinship in Canada” about a year ago.

Guest Biographies

Ken Popert lives in Toronto, where he was born in 1947. He began his lifelong career in gay activism as a graduate student at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY USA in 1968. Returning to Toronto in 1973 he became a leading member of The Body Politic Collective, writing and editing for the widely influential ‘gay liberation journal,’ and he met his current partner, Brian Mossop, at the city’s 1974 gay pride march. Upon its demise in 1986, the Collective entrusted the future of its non-profit enterprise to him, which he led as president and executive director until his retirement in 2017.

Jeff Iovannone is a queer historian and historic preservation planner from Buffalo, New York. He is co-founder of Gay Places, an initiative that documents LGBTQ historic sites in Western New York, with Preservation Buffalo Niagara. He is currently working on a Master’s degree in historic preservation planning at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Follow Jeff on Instagram @drjeffqueerhistorian.

Episode Notes

- Ken tells us about his background, how he ended up at Cornell where he majored in linguistics with a minor in anthropology, and how he became involved in gay student activism.

- Jeff asks Ken to describe Cornell in the 1970s and what it was like for gay and lesbian students at the time, and how he became involved with the Cornell Gay Liberation Front.

- Ken talks about the house parties that people would drive miles to attend where gay people in Ithaca could socialize and be themselves, rather than going out to a public/private space like Morrie’s Tavern.

- Ken became the editor of a campus newsletter, which is how he become involved in gay journalism for the rest of his life.

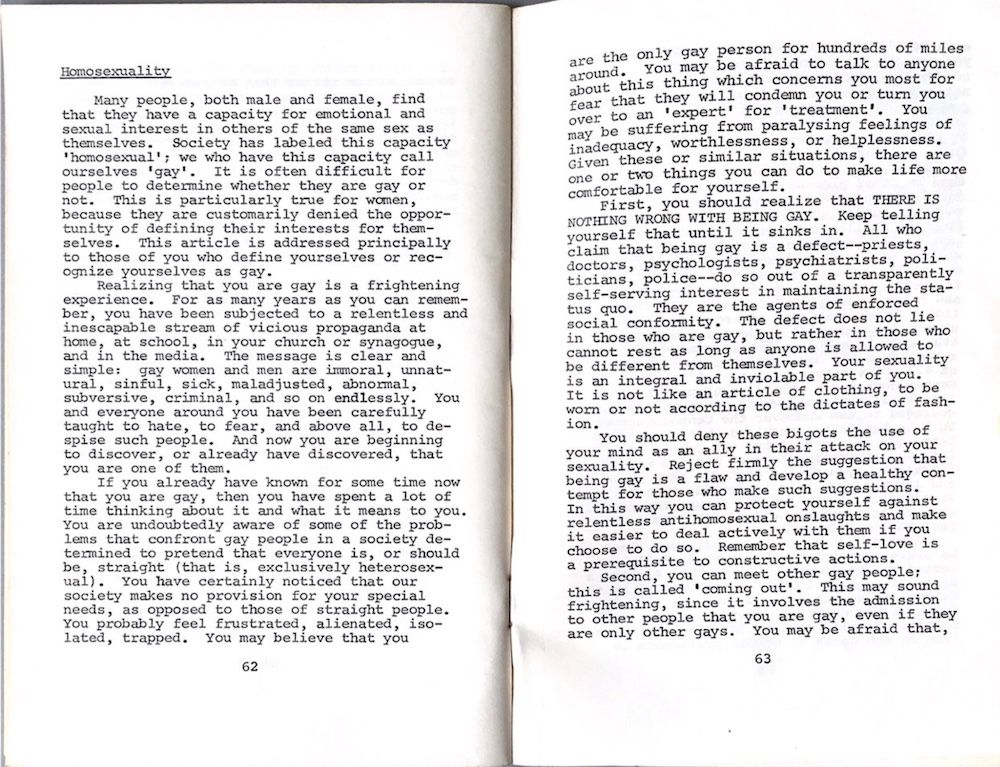

- We speak about the role of progressive, empowering language used in the chapter, “Homosexuality” in “Sex Information for Cornell Students” that Ken co-authored with Jane Gallop.

“Sex Information for Cornell Students.” August 1972. Courtesy Ken Popert.

- Ken then shares his thoughts on a statement that I. F. Stone (a famous anti-war journalist) made at an anti-war rally he attended: “This may be therapeutic, but is it politics?” Ken explains,

“That has really stuck with me to ask that about everything. Is this about making yourself feel good, or is this about making change happen. Of course, they can be the same thing. It’s easy to fall into thinking you’re doing something important just to make people feel better about themselves.”

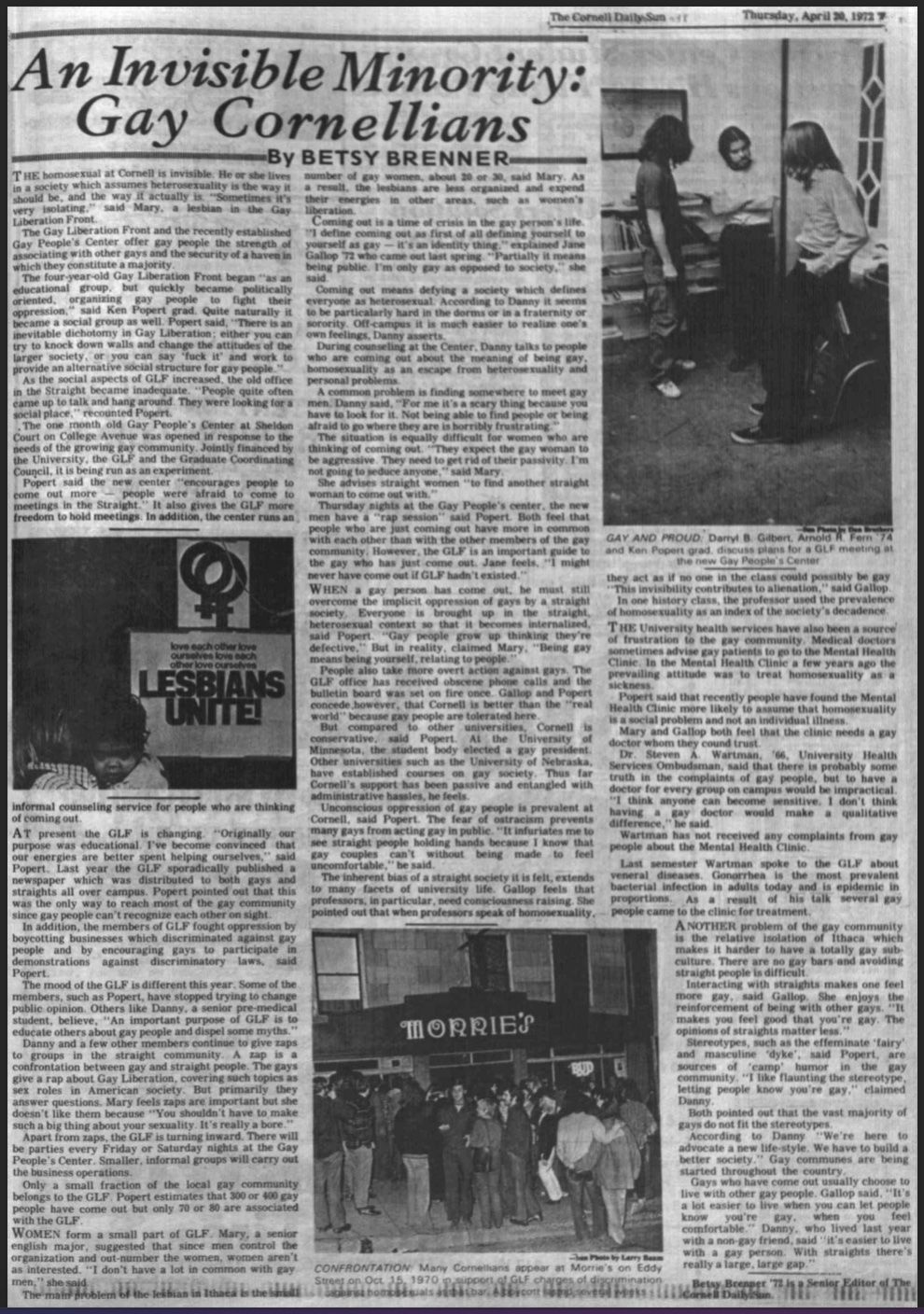

- Ken was quoted in a 1972 Cornell Daily Sun article entitled “An Invisible Minority: Gay Cornellians” saying he thought gay students needed to focus more on helping each other than public education.

- Aside from Willard Straight and the Gay People’s Center, Jeff asks Ken where else other gay people (not just students) were socializing in Ithaca. Ken talks about what happened at the Gay People’s Center; the services, events, and meetings for writing the newsletter.

- I ask Ken to discuss how his experiences at Cornell shaped or influenced his return to Toronto and then his involvement at The Body Politic (TBP) starting in February 1973. Ken was attracted to the recently founded TBP because of his involvement in writing the newsletter at Cornell. He wanted to affect the world through journalism and advocacy, and the ability to speak to an “unseen audience.” He was fascinated by the question, “How do you move people to political action through writing” — a perfect fit with TBP which dubbed itself “A Gay Liberation Journal.”

- We talk about the Bathhouse Raids protests on Yonge Street in Toronto when the protestors raged against the police, TBP’s role in organizing the protests, and Ken’s experience — and being hit by a police car.

- Ken speaks to the development of the Gay Liberation Movement Archives (now the Arquives) while at TBP, and why it was so important to preserve the lessons of history that demonstrated that resistance was not a new thing (i.e., that Stonewall wasn’t the beginning or queer history, rather it was a continuation and a rebirth).

“You have to know your history so that you know what you’re capable of.”

- I share my experience working at Pink Triangle Press (1993–2004) and my relationship with Ken as a boss, a mentor, and how he influenced me and the work I’m doing now. (We also have some fun at my expense about my “hyper-neatness,” both in my time at PTP, and the state of my office in the background.)

- I ask Ken to share what he thinks is one of the most significant lessons he can offer today. Ken notes that,

“Progressive politics today is obsessed with image-making and obsessed with language, almost to the exclusion of the real world locked inside its own bubble. It can be very comfortable to spend all your time with people who agree with you about everything, but it’s not politics. Politics is about engaging the outside world in a constructive fashion in the hope of growing your bubble — not building a wall around it. My concern is, people have to come back to, how do we speak to the conservative people. In the United States, how do we speak to the large segment of the population that is so alienated that they will vote for Donald Trump.”

Links & references mentioned on the show.

- Ken Popert to step down as executive director of Pink Triangle Press

- Pink Triangle Press: A History 1971–2021

- Interview with the Authors of “Out North: An Archive of Queer Activism and Kinship in Canada” — Authors Craig Jennex & Nisha Eswaran on the Think Queerly Podcast

- “Queer Progress: From Homophobia to Homonationalism.” Tim McCaskell

Historical Background of Gay Activism at Cornell

Prepared by Jeffry J. Iovannone

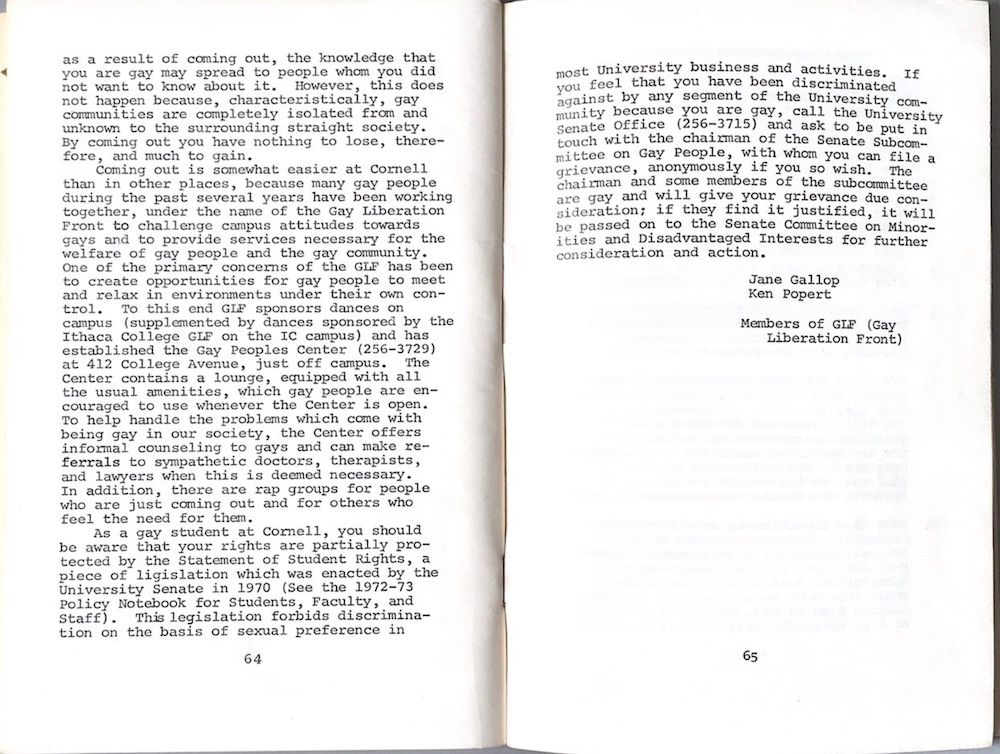

Cornell, an Ivy League university founded in 1865, is located in Ithaca, a small city in Central New York on the southeastern end of Lake Cayuga, the largest of the eleven Finger Lakes. The Cornell Student Homophile League, the second gay student organization in the United States, was founded in May 1968. By 1970, the organization changed its name to Cornell Gay Liberation Front to reflect the “out and proud” stance of the broader Gay Liberation Movement. “We’re gay and we’re proud of it,” wrote Cornell GLF members, announcing the group’s name change in their October 1970 newsletter. “Heterosexuals are welcome at our meetings, but none of us is going to play straight to make anyone feel more comfortable,” they continued. “The beautiful, gay people on this campus are finally getting themselves together, and the new Gay Liberation Front is a symbol of that change.”

Cornell GLF initially met in 24 Willard Straight Hall, the student union located on Cornell’s central campus, but students had few expressly gay spaces to socialize.

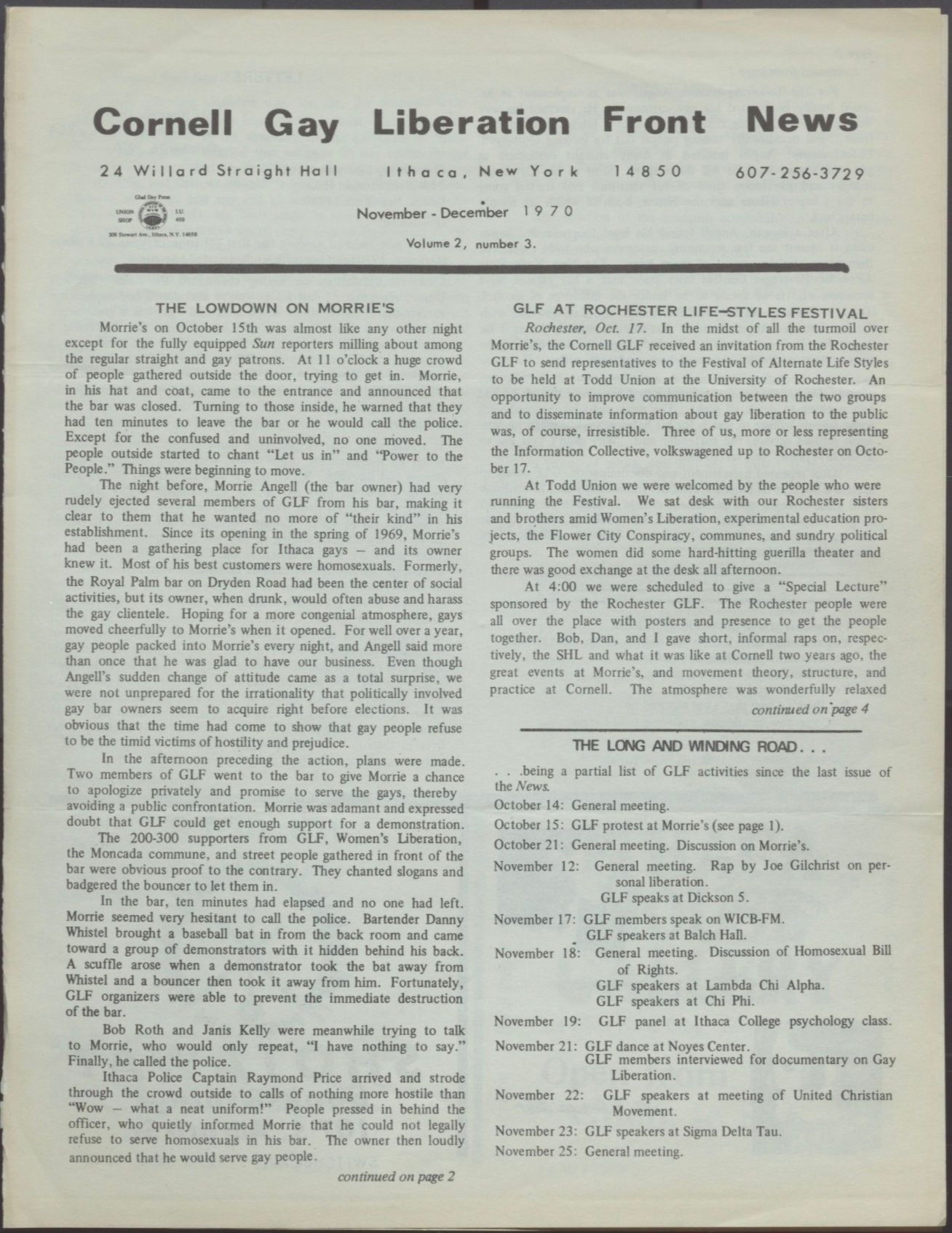

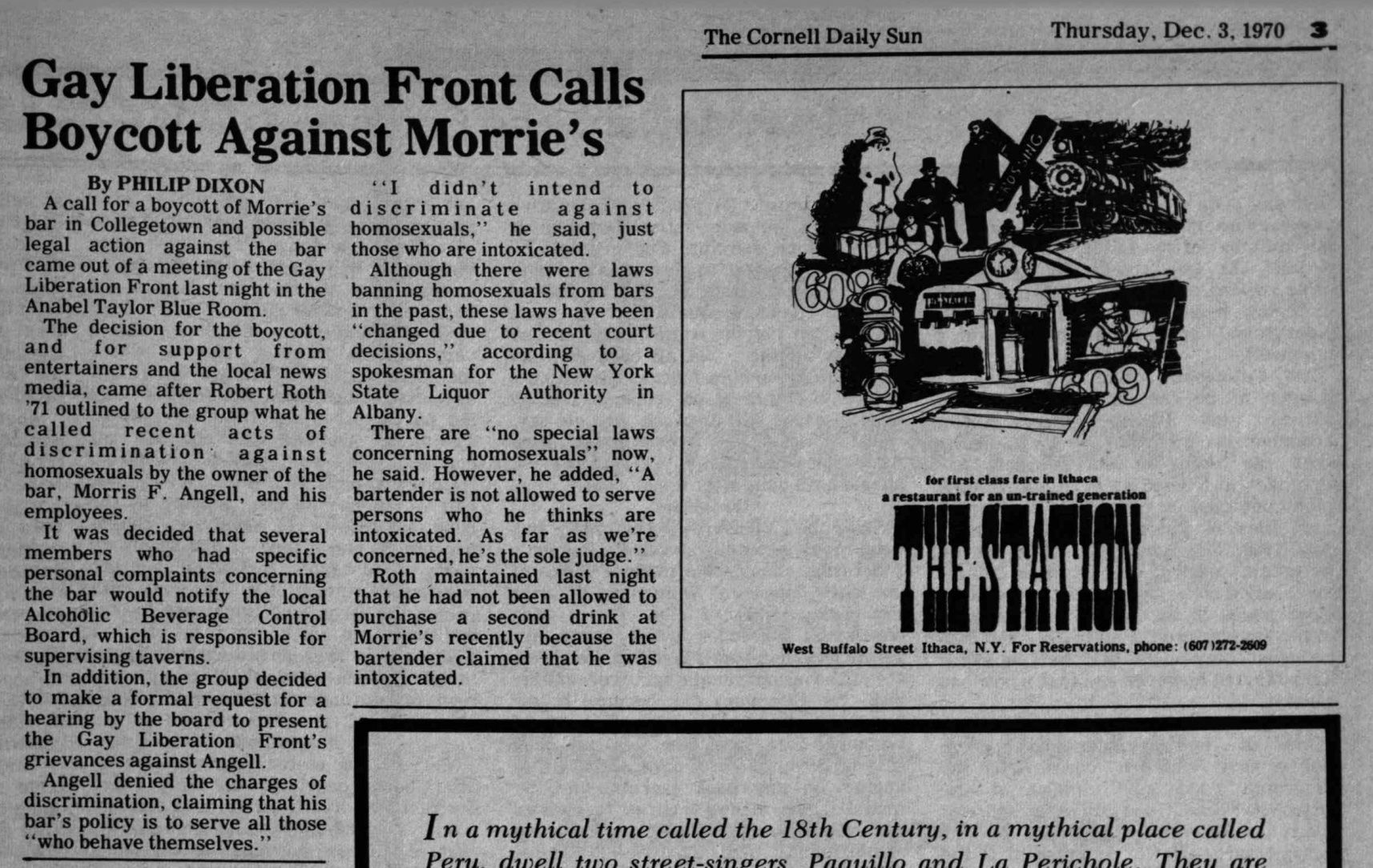

When a new bar, Morrie’s, opened at 409 Eddy Street in Collegetown in the spring of 1969, gay and lesbian Cornellians decided to make the bar their own. Morrie’s was even listed in several editions of the Bob Damron’s Address Book, a travel guide aimed at gay men, during the early 1970s. Morris F. Angell, the bar owner, initially welcomed their business but became hostile over fears Morrie’s growing reputation as a gay bar would damage his involvement in local Democratic politics. Following multiple instances of discrimination wherein Angell ejected Cornell GLF members from his bar, the organization called for a boycott. Conflict between the bar and gay and lesbian students and local residents culminated in a 200–300 person demonstration on October 15th of 1970. The Morrie’s demonstration is considered the first gay student protest in the United States.

Morrie, however, never fully welcomed gay people into his establishment.

Though he legally couldn’t ban customers based on their sexual orientation, he exploited a loophole in the New York State Alcoholic Beverage Control Laws that stated a bar cannot serve someone who appears under the influence of alcohol, that determination being left to the bar owner. Angell began expelling suspected gay patrons under the pretense of intoxication. By March of 1971, Cornell GLF concluded their boycott after Angell, following negotiations with the GLF, issued a statement saying, “I do not seek to discriminate against anyone. You have my personal assurance that pleasant and efficient service is available to all customers at all times.” Many gay and straight patrons alike grew tired of Morrie’s antics and moved on to other Ithaca bars, such as The Chapter House and The Haunt, or focused on gay-run spaces like the GLF Gay People’s Center. Morrie’s eventually closed in September 1976.

Some Cornell GLF members, like Linguistics graduate student Ken Popert, were less interested in taking over bars like Morrie’s and thought gay students and community members needed a space they controlled. Under the leadership of Cornell GLF, the Ithaca Gay People’s Center opened at Sheldon Court on 410 College Avenue in April 1972 (the center later relocated to 306 East State Street). Open to students at Cornell, Ithaca College, and residents, the Gay People’s Center became the place from which Cornell GLF enacted the four central facets of their mission: education, peer counselling via the organization’s “Gayline,” social opportunities, and political engagement. The center was jointly financed by the University, Cornell GLF, and the Graduate Coordinating Council.

In an article about gay Cornellians from The Cornell Daily Sun, Cornell’s student newspaper, Popert explained the center “encourages people to come out more — people were afraid to come to meetings in the Straight [Willard Straight Hall]… Originally our purpose was educational,” he continued, “I’ve become convinced that our energies are better spent helping ourselves.”

GLF member Jane Gallop similarly noted that due to Ithaca’s geographic isolation in central New York, it was difficult for a gay subculture to form. Gallop found it affirming to interact with other gay people because, in her words, “it makes you feel good that you’re gay. The opinions of straights matter less.” The Gay People’s Center strove to provide a space where gay and lesbian Cornellians and local Ithacans could feel just that. The center was not without controversy, however, and faced several acts of vandalism and harassing phone calls. Nevertheless, gay (and later, LGBTQ) advocacy at Cornell could not be stopped.

See here for a brief timeline of LGBTQ+ history at Cornell.

Selected Primary Sources

- “Name Change,” Cornell Gay Liberation Front News, Vol. 2, №2, October 1970.

- Philip Dixon, “Gay Liberation Front Calls Boycott Against Morrie’s,” The Cornell Daily Sun, December 3, 1970.

- “Boycott Morrie’s,” The Cornell Daily Sun, December 4, 1970.

- “The Lowdown On Morrie’s,” Cornell Gay Liberation Front News, Vol. 2, №3, November-December 1970.

- “GLF Concludes Boycott of Bar,” The Cornell Daily Sun, March 1, 1971.

- Betsy Brenner, “An Invisible Minority: Gay Cornellians,” The Cornell Daily Sun, April 20, 1972.

Ken Popert Image Credit: Adam Coish

Member discussion